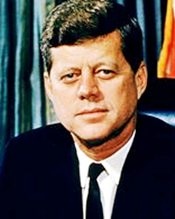

The Presidents of the USA

| Born | May 29, 1917, Brookline, Mass. |

| Political party | Democrat |

| Education | • Harvard College, A.B., 1940 • Stanford Business School, 1940 |

| Military service | U.S. Navy, 1941-45 |

| Previous public office | ♦ House of Representatives, 1949-53 ♦ U.S. Senate, 1953-60 |

| Died | Nov. 22, 1963, Dallas, Texas. |

Kennedy was the second son of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy and Joseph P. Kennedy. His father was a financier and former chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission who was active in the Democratic party. John Kennedy was voted “most likely to succeed” at the Choate School. After serving for a time as secretary to his father, who in 1937 had been appointed ambassador to Great Britain by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Kennedy graduated from Harvard in 1940. His senior thesis, “Appeasement at Munich,” a study of the British appeasement of Adolf Hitler, was awarded high honors. It was published that same year under the title Why England Slept, becoming a bestseller.

Kennedy enlisted in the navy in October 1941, and on August 2, 1943, his PT Boat 109 was sunk by a Japanese destroyer. Two of the crew died, but Kennedy helped to rescue his 10 surviving crew members and was awarded the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps medal and a Purple Heart for injury. He returned home a hero, though a naval inquiry into the sinking indicated poor seamanship and command on Kennedy's part.

In 1945 Kennedy was discharged from the navy, worked briefly as a reporter for the Hearst newspapers, and the following year won election to the House of Representatives from a district in Boston. He was reelected twice and in 1952 defeated incumbent Republican Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., for a Senate seat. Kennedy's accomplishments in Congress were minimal. He had one of the worst attendance records, which may have been due to his having Addison's disease, which required daily implantation of a steroid compound in his thighs.

Kennedy had a spinal operation in 1954, and while recuperating he wrote Profiles in Courage, a series of biographies of American politicians who had gone against public opinion to do what they believed was right. It was published in 1955 and won a Pulitzer Prize for biography the following year. In 1956 Kennedy campaigned for the Vice Presidential slot on the Democratic ticket, but the convention nominated Estes Kefauver instead. Later, Kennedy would say that losing that contest was the best thing that could have happened to him, because the Democratic ticket went down to a crushing defeat. Kennedy was reelected to the Senate by a large margin and began organizing a campaign for the next Presidential nomination.

In 1960 he was nominated by the Democratic convention on the first ballot, defeating Senate majority leader Lyndon Johnson handily. He then offered Johnson the second spot on the ticket, and to the surprise of many of Kennedy's advisers, Johnson accepted. Kennedy's July 15 acceptance speech offered Americans a “New Frontier” and promised “to get America moving again.”

In the November election Kennedy and Johnson won a majority of electoral college votes against Republican nominee Richard M. Nixon but they received less than half the popular vote. At age 43, Kennedy was the youngest man ever elected President (though Theodore Roosevelt had been a year younger when he succeeded to the office).

“Ask not what your country can do for you,” Kennedy said in his inaugural address, “ask what you can do for your country.” He challenged youthful idealists to join the Peace Corps, which he created by executive order a few weeks later, to help with the development of other nations. He got Congress to create an Alliance of Progress in Latin America to provide foreign aid in the Western Hemisphere. He created an arms control agency to pursue arms limitations talks with the Soviet Union. He challenged the nation to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade, a feat accomplished in 1969, right on schedule.

Kennedy's New Frontier legislative program was designed to get the U.S. economy moving again after the recession and slow growth of the years under Dwight Eisenhower. It emphasized an investment tax credit and other tax breaks for business. His proposed social programs were extensions of the New Deal: federal aid to education, medical care for the elderly, urban mass transit, a new Department of Urban Affairs, and regional development for Appalachia. Much of this legislation was stalled in Congress by a coalition of Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats, though Congress did pass an increase in the minimum wage, higher Social Security benefits, and a public housing bill.

It also passed a trade expansion act that significantly increased U.S. exports and opened up foreign markets.

Kennedy's refusal to provide for aid to parochial (church-run) schools in his federal aid to education bill doomed its chances. In 1962 Kennedy sent federal troops to Mississippi to ensure that James Meredith, an African-American student, could enroll at the University of Mississippi and attend classes without harassment.

In 1963 he used federal troops in Alabama to enforce federal court desegregation orders. But Kennedy delayed introducing civil rights legislation until late spring 1963.

On August 28, 1963, a March on Washington for Peace and Justice, which attracted more than 200,000 people, convinced Kennedy to push Congress harder for comprehensive civil rights laws. In a televised speech Kennedy identified with the marchers, saying that the grandchildren of the slaves freed by Lincoln “are not yet freed from the bonds of injustice … and this nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free”.

On April 17, 1961, an operation sponsored by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) against Cuban communist leader Fidel Castro began: 1,500 Cuban exiles landed in Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, hoping to spark an uprising. They were surrounded and defeated by the Cuban army. At the last minute Kennedy refused to provide them with air cover for their operation in order to avoid overt U.S. involvement. Kennedy accepted full responsibility for the fiasco. The 1,100 prisoners held by Castro were ransomed by the United States for $53 million in food and medical supplies.

After East Germany constructed the Berlin Wall to seal off the communist side of the city from the West in August 1961, Kennedy traveled to Berlin to show solidarity with its citizens. He proclaimed in German, “Ich bin ein Berliner” (I am a Berliner).

In October 1962 Kennedy found out that the Soviet Union had shipped offensive missiles and bombers to Cuba; after quarantining the island with U.S. naval forces, he insisted that the Soviets remove their offensive forces, and after a tense standoff they did so. In August 1963 Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which banned nuclear testing in the atmosphere, outer space, and the oceans. Only underground testing, which presented no risk of radioactive fallout, would be permitted.

Kennedy ordered U.S. military advisers and trainers to South Vietnam, 18,000 in all, to prop up a pro-American government against attempts by communist guerrillas to undermine it. But he also decided to allow South Vietnamese military units to overthrow President Ngo Dinh Diem and install a new military leader. Although Kennedy hoped the new regime would improve the situation, the November 1, 1963, coup began a prolonged period of instability in South Vietnam that all but ensured that U.S. troops would be needed for the war.

On November 22, 1963, while visiting Dallas, Texas, to help unify the feuding state Democrats, John Kennedy was shot and killed by two bullets fired from the Book Depository building while riding in a motorcade through the center of town. Texas governor John Connally was wounded. Lee Harvey Oswald, the suspected assassin, was taken into custody by Dallas police, but two days later he was killed by Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby while being transferred from his cell to an office for questioning. A national commission headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren concluded that Oswald, acting alone, had shot the President in the rear of the head with a rifle and that Oswald had been mentally ill.

The Kennedy era was brief. It began the transition from an era of confrontation to an era of negotiation in the cold war. Kennedy was the first President born in the 20th century: his youth, vigor, and style under pressure created a “Camelot on the Potomac” for a generation of Americans who came of age during World War II and the first years of the cold war.

The debate over what Kennedy would have done had he lived continues. He offered some statements favorable to hawks, others to doves. His actions, however, dramatically increased the U.S. military role in Vietnam and emphasized it as the test case against Communist wars of “national liberation.” At the end, ambiguity marked his presidency, as mystery shrouded his assassination.

His murder made him a martyr, and his image and that of his administration were romanticized by his friends and family. Despite later revelations that his personal life was less than impeccable, Kennedy remains a figure of reverence in the eyes of many Americans.