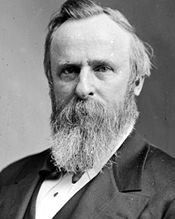

The Presidents of the USA

| Born | Oct. 4, 1822, Delaware, Ohio |

| Political party | Whig, then Republican |

| Education | • Kenyon College, B.A., 1842 • Harvard Law School, LL.B., 1845 |

| Military service | Ohio Volunteers, 1861-65 |

| Previous public office | ♦ solicitor of Cincinnati, 1858 ♦ House of Representatives, 1865-68 ♦ Governor of Ohio, 1868-72, 1876-77 |

| Died | Jan. 17, 1893, Fremont, Ohio |

Hayes never knew his father, who died before his birth. After graduating at the head of his class from Kenyon College and completing his legal studies at Harvard, Hayes practiced law in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he was active in the Whig party. He became a Republican in 1856.

During the Civil War he commanded an Ohio regiment, fought in six major campaigns, and received a medal “for gallant and distinguished services.” At the Battle of Winchester he captured an artillery position in hand-to-hand fighting. In the Battle of South Mountain he suffered a severe arm wound that ended his military career.

Hayes was then elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he supported the moderate wing of his party, which wished for conciliation with the South, rather than the radical Republicans, who intended to impose a harsh military occupation on the defeated region. He served three terms as governor of Ohio, providing honest and competent government. But Hayes failed in his efforts in 1868 to amend the state constitution to allow African Americans to vote.

In 1876, as a dark horse candidate, Hayes defeated James G. Blaine for the Republican nomination for President. In his letter accepting the nomination, he pledged that he would not be a candidate for a second term.

In 1876, Hayes was elected president in one of the most contentious and hotly disputed elections in American history:

At first it appeared that Democrat Samuel J. Tilden was the winner. But Republicans challenged the results in Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina. These states had 20 electoral votes—enough for Hayes to win the White House.

Hayes believed that many African Americans had been intimidated from voting and that fraud had been committed. In South Carolina, for example, the number of votes counted was larger than the state's population. The Republican Senate and Democratic House created a 15-member electoral commission to examine the returns from these states and to certify which electoral votes—Democratic or Republican—it would accept as valid. The commission awarded all 20 of the contested electoral votes from these states to Hayes by a party-line vote of 8 to 7. On March 2, 1877, the commission declared Hayes elected by 185 to 184 electoral college votes.

Indignation over the obviously partisan decision affected Hayes's administration, which was generally conservative and efficient but no more than that.

In what historians have termed the “great betrayal” of African Americans, the Southern Democrats agreed to accept the election of Hayes in return for the withdrawal of all federal troops from Louisiana and South Carolina, thus ending Reconstruction. The troops were withdrawn within two months of Hayes's inauguration. Republicans abandoned black voters, and without federal protection, white supremacy in politics and the segregation of public accommodations soon occurred. Republicans also promised the South financing for a transcontinental railroad line to link Southern and Western markets.

Early in his Presidency Hayes lost any chance of popular support through his actions during the railroad strikes of 1877. Workers faced wage cuts on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and they went on strike. At the request of the governor of West Virginia, Hayes sent federal troops to guard the mails and ensure the safety of trains. Rail strikes spread to Baltimore, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and other cities. Eventually, the workers gave in to management, but the resentment against Hayes's use of troops led to the first congressional investigation of labor-management relations.

Hayes had campaigned for President as a reformer, distancing himself from the corrupt Grant administration. “He serves his party best who serves his country best,” he said in his inaugural address. Once in office, he alienated members of his party by making merit appointments and reforming government departments.

Because of the opposition of New York party leader Senator Roscoe Conkling, it took Hayes two years to secure the dismissal for mismanagement of Chester A. Arthur as collector of the Port of New York. But Conkling (whom he had defeated for the nomination in 1876) was able to thwart Hayes's efforts to obtain civil service legislation.

After the 1878 midterm election Democrats controlled both houses of Congress, and Hayes had little influence in the legislature. He often vetoed legislation passed by Congress. His most notable vetoes included the Bland-Allison Act, which required the resumption of silver coinage (Congress passed the bill over his veto); “riders” to appropriations bills sponsored by Southern Democrats that would have nullified federal election laws protecting black voting rights in Southern states; and a bill to exclude Chinese immigrants, on the grounds that it violated the Burlingame Treaty of 1868, an agreement between the United States and China that precluded the United States from a total exclusion of Chinese immigrants. Hayes bowed to anti-Chinese sentiment and negotiated a new treaty with China that limited immigration.

Hayes opposed a French scheme to build the Panama Canal, claiming it was a violation of the Monroe Doctrine. He sent a special message to Congress stating that “the policy of this country is a canal under American control.” When the French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps formed an “advisory committee” in the United States and paid the secretary of the navy, Richard W. Thompson, $25,000 to serve, Hayes put an end to this effort to buy influence in the capital by firing Thompson. De Lesseps tried to build his canal anyway but eventually abandoned the project.

Hayes dealt with several conflicts with Indian tribes. The Nez Perce, led by Chief Joseph, began an uprising in June 1877 when Major General Oliver O. Howard ordered them to move on to a reservation. Howard's men defeated the Nez Perce in battle, and the tribe began a 1700-mile retreat into Canada. In October, after a decisive battle at Bear Paw, Montana, Chief Joseph surrendered and General William T. Sherman ordered the tribe transported to Kansas, where they were forced to remain until 1885.

The Nez Perce war was not the last conflict in the West, as the Bannocks rose up in Spring 1878 and raided nearby settlements before being defeated by Howard's army in July of that year.

War with the Ute tribe broke out in 1879 when the Utes killed Indian agent Nathan Meeker, who had been attempting to convert them to Christianity. The subsequent White River War ended when Schurz negotiated peace with the Utes and prevented the white Coloradans from taking revenge for Meeker's death.

In other foreign matters, Hayes ordered U.S. troops into Mexico to end raids by Indians, eventually obtaining cooperation from Mexican authorities so that troops could be withdrawn. He negotiated a treaty with Samoa that gave the U.S. Navy the use of the port of Pago Pago.

In 1880 despite his growing popularity, Hayes refused to run for a second term and honored his pledge not to seek reelection. He returned to his home in Fremont, Ohio, where he promoted educational reforms, especially for African-American industrial education in the South.

From 1883 on, he served as president of the National Prison Association, an organization established to promote improvements in the correctional system.

Hayes proved a surprisingly effective president, ending military occupation of southern states; reforming the civil service, putting the country back on the gold standard, and suppressing railroad strikes.

He was generally conservative and efficient but no more than that.