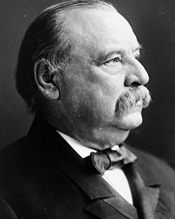

The Presidents of the USA

| Born | Mar. 18, 1837, Caldwell, N.J. |

| Political party | Democrat |

| Education | • Law studies, 1855-59 |

| Military service | none |

| Previous public office | ♦ ward supervisor, Erie County, N.Y., 1863 ♦ assist. district attorney, Erie County, 1863-65 ♦ Erie County sheriff, 1871-73 ♦ mayor of Buffalo, 1882 ♦ governor of New York, 1883-84 |

| Died | June 24, 1908, Princeton, N.J. |

The son of a Presbyterian minister, Cleveland helped support his family by working in a local grocery store beginning at age 14. He worked on his uncle's farm in Buffalo, then studied law. He became assistant district attorney of Erie County during the Civil War, hiring a substitute to fight for him for $300 when he was drafted, a frequent and legal procedure at the time.

In 1865 he was defeated in his first election bid when he ran for district attorney of Erie County.

Cleveland became sheriff in 1870, a post which promised large fees as well as frustrating experiences with corruption. Although he was respected for his handling of official responsibilities, he made many enemies. After 3 years, he returned to his legal practice.

Nine years later he was elected mayor of Buffalo.

In his one-year term as mayor he stood for honesty and efficiency - exactly the qualities the New York Democrats sought in a candidate for governor in 1882.

Cleveland became governor and favored reform legislation confronting the interests of the New York-based political machine called Tammany Hall and its "boss," John Kelly, to such an extent that it caused a rift between them.

After one term as governor, Cleveland was seen as a leading contender for the presidential nomination of 1884. His advantages lay in his having become identified with honesty and uprightness; also, he came from a state with many votes to cast, wealthy contributors, and a strong political organization. Against the Republican nominee James G. Blaine, Cleveland even won the support of reform-minded Republican dissidents known as Mugwumps.

As President, Cleveland was a conservative in budget matters and a reformer when it came to patronage and the civil service. He expanded the classified “merit appointment” list of the civil service by 85,000 positions. His cabinet and other high-level appointments owed less to patronage and politics and more to merit.

His new secretary of the navy, William Whitney, built a modern steel navy that proved its worth to future Presidents.

He vetoed 200 of the 1,700 private pension bills Congress passed for veterans of the Civil War, arguing that many of these claims were fraudulent.

He also vetoed measures to relieve farmers in the West from drought because he did not believe that the national government had the responsibility under the Constitution to solve the problems of people in need.

Cleveland in his first term advocated improved civil service procedures, reform of executive departments, curtailment of largess in pensions to Civil War veterans, tariff reform, and ending coinage based on silver. He failed to stop silver coinage but achieved at least modest success in the other areas

in 1887 Cleveland took a strong position on tariff reform and later supported passage of the Mills Bill of 1888. Although the Mills Bill provided for only moderate tariff reductions, it was viewed as a step in the right direction,

Although Cleveland's administration was free of scandal and corruption, he was not all that popular. In 1888, running against a high-tariff candidate, Republican Benjamin Harrison, he won a majority of the popular vote but lost in the electoral college, in part because he failed to carry New York.

After leaving the White House, Cleveland practiced law in New York City for four years, a period he described as the happiest in his life. In 1892, Cleveland was nominated by the Democrats a third time, and he won the rematch with Harrison. Cleveland ran on a platform of good government, lower tariffs, and a return to using only gold (rather than silver) to back the paper currency issued by the U.S. Treasury.

It was a quiet campaign, with the Democrats aided by the 1892 Homestead strike, in which prominent Republicans were involved in the effort to break labor power and to maintain special benefits for the powerful steel magnates. The Democrats scored smashing victories in 1892, not only electing Cleveland but winning control of both House and Senate.

His victory made him the only American President to serve two nonconsecutive terms.

Cleveland's eventful second term was a contrast to his first.

Cleveland had scarcely taken his oath of office when the worst financial panic in years broke across the country. A complex phenomenon, the Panic of 1892-1893 had its roots in over expansion of United States industry, particularly railroad interests; in the long-term agricultural depression that reached back to the 1880s; and in the withdrawal of European capital from America as a result of hard times overseas.

The crisis led to calls from populists and progressives for national government programs to regulate the banks, but Cleveland turned a deaf ear. He refused to inflate the currency and forced repeal of the Silver Purchase Act, which had guaranteed that the government would purchase a set amount of silver from mine owners each year. This led to a contraction in the supply of money that worsened already hard times in the West.

Beset by currency and tariff failures and hated by a large segment of the general population and by many in his own party, Cleveland further suffered loss of prestige by his actions in the Pullman strike of 1894. Convinced that the strike of the American Railway Union under Eugene Debs against the Pullman Company constituted an intolerable threat to law and order and that local authorities were unwilling to take action, Cleveland sent Federal troops to Chicago and sought to have Debs and his associates imprisoned. Although Cleveland prevailed and order was enforced, laborers throughout the country were angered by this use of Federal force.

In foreign affairs Cleveland refused to accept a petition from a white settlers’ government that Hawaii be annexed by the United States, accurately describing the local “Committee of Safety” as unrepresentative of the native population and not elected by it.

In 1895 he insisted that the British government accept an American determination of the boundary between Venezuela and British Guyana. Ultimately, the British and Venezuelans negotiated an end to their boundary dispute, and arbitration upheld most of the British claim. Cleveland refused to intervene in the Cuban revolt against Spanish rule, leaving the problem for his successor. When there was talk in Congress of declaring war against Spain, Cleveland let it be known that as commander in chief he would refuse to use the military to fight such a war. He also rejected the idea that the United States buy Cuba from Spain. Instead, he proposed that the Spanish offer “genuine autonomy” to the Cubans.

By 1896 Cleveland's leadership was repudiated by his own party. A coalition of populists and silver Democrats, who were interested in aid to farmers, regulation of business, and increased use of silver coins as currency, dominated the party convention. It turned away from conservative policies and nominated the fiery populist William Jennings Bryan.

Cleveland retired to Princeton, N.J., as soon as his term ended. He occupied himself with writing, occasional legal consultation, the affairs of Princeton University, and very occasional public speaking.

After 1900 he became less reluctant to appear in public. Sympathetic crowds greeted his appearances as the conservative Democratic forces with which he had been identified took party leadership from William Jennings Bryan. Briefly stirred into activity in 1904 to support Alton B. Parker's candidacy for the presidency, Cleveland spent most of his retirement years outside political battles, increasingly honored as a statesman.

After offering to assist President Theodore Roosevelt in an investigation of the anthracite coal strike of 1902, he was active in the reorganization of the affairs of the Equitable Life Assurance Society in 1905.

His death in 1908 was the occasion for general national mourning.

Cleveland is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms (1885-1889 and 1893-1897) and therefore is the only individual to be counted twice in the numbering of the presidents.

Also, he was the only Democrat elected to the presidency in the era of Republican political domination that lasted from 1861 to 1913. The only President to be married in the White House. In dealing with Congress and state governors, he was the strongest President since Abraham Lincoln.

Cleveland was the leader of the pro-business Bourbon Democrats who opposed high tariffs, Free Silver, inflation, imperialism and subsidies to business, farmers or veterans. His battles for political reform and fiscal conservatism made him an icon for American conservatives of the era.

Cleveland won praise for his honesty, independence, integrity, and commitment to the principles of classical liberalism. He relentlessly fought political corruption, patronage, and bossism. Indeed, as a reformer his prestige was so strong that the reform wing of the Republican Party, called "Mugwumps", largely bolted the GOP ticket and swung to his support in 1884

His support of the gold standard and opposition to Free Silver alienated the agrarian wing of the Democratic Party. Furthermore, critics complained that he had little imagination and seemed overwhelmed by the nation's economic disasters -depressions and strikes- in his second term.

Even so, his reputation for honesty and good character survived the troubles of his second term. Biographer Allan Nevins wrote: "in Grover Cleveland the greatness lies in typical rather than unusual qualities. He had no endowments that thousands of men do not have. He possessed honesty, courage, firmness, independence, and common sense. But he possessed them to a degree other men do not.