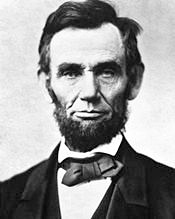

The Presidents of the USA

| Born: | Feb. 12, 1809, near Hodgenville, Ky. |

| Political party | Whig (in Congress); Republican |

| Education | largely self-educated |

| Military service | Illinois volunteer regiment, 1832 |

| Previous public office | ♦ postmaster, New Salem, Ill., 1833-36 ♦ Illinois General Assembly, 1834-41 ♦ House of Representatives, 1847-49 |

| Died | Apr. 15, 1865, Washington, D.C. |

Lincoln was born in a log cabin in Kentucky in a typical pioneer family. He was the first President born outside the original 13 states that formed the Union. When he was seven, his family moved to another log cabin in Indiana, where his father cleared and farmed 160 acres. His mother died when he was nine and his father married Sarah Bush Johnston, whose three children moved into the log cabin with Lincoln and his sister, Sarah.

He later reckoned that his total schooling did not exceed one year, but being unusually ambitious he pursued self-improvement through reading and longed for a better life. After his farm chores young Abe educated himself by lantern light, borrowing books from neighbors and nearby towns.

He grew to his full size of six feet, four inches and gained a reputation not only as a scholar but also as a wrestler and axeman.

At age 22 Lincoln struck out on his own and settled in New Salem, Illinois. He worked as a storekeeper and was a captain in a campaign against the Black Hawk Indians, but he saw no action and his store failed. He then worked as a surveyor and postmaster. He lost a contest for the state legislature in 1832 (“The only time I have ever been beaten by the people,” he later said), but he was elected two years later on the Whig ticket. He also studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1836.

Lincoln became a successful lawyer in Springfield, and his clients included the Illinois Central Railroad and other corporations. In 1839 he met Mary Todd, and they married in 1842.

Lincoln entered national politics in 1846, when he was elected as a Whig to the U.S. House of Representatives. He introduced a bill to end slavery in the nation' capital, but it was never brought to a vote. His support for the Wilmot Proviso (a bill to outlaw slavery in territories acquired from Mexico), his opposition to the Mexican-American War (he voted for a resolution in Congress that described it as “a war unconstitutionally and unjustly begun by the President”), and his campaigning for Zachary Taylor in the election of 1848 were unpopular positions in Illinois, and he declined to seek reelection.

In various speeches in 1854, Lincoln opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Bill sponsored by Senator Stephen A. Douglas. The bill provided for a popular vote on the question of slavery in each of the territories. In two debates with Douglas, Lincoln argued that the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which forbade slavery north of Missouri's southern boundary, should be retained. He argued that only in free states could poor white workers improve their circumstances, because there they would not be competing against slave labor.

Lincoln failed in a bid to obtain a Senate seat in 1855, but the following year he helped organize the Republican party and nearly won its Vice Presidential nomination. In 1858 Lincoln challenged Douglas for his Senate seat. “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” he told the Illinois Republican party convention in his acceptance speech, adding “I believe this Government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free.” In a second series of Lincoln-Douglas debates held around the state, Lincoln hammered at Douglas for ignoring the moral dimension of the slavery question, calling slavery a “moral, social and political evil.” Lincoln lost the election but gained a national reputation.

In February 1860 Lincoln delivered an antislavery speech in New York City and was applauded by his audience and by New York newspapers, which made him a contender for the Republican Presidential nomination. In May, he won the nomination by defeating the favorite, William H. Seward, on the third ballot, after his campaign managers promised cabinet positions to politicians from Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania.

The Whigs nominated John Bell, the Northern Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas, and the Southern Democrats bolted from their party to nominate John C. Breckinridge. Lincoln, along with Vice Presidential nominee Hannibal Hamlin, was elected with a 39.8 percent plurality of the popular vote but a large majority in the electoral college. He said farewell to his friends in Springfield and took a train east. Because of a plot against his life, he left his train in Philadelphia and arrived without notice in Washington, D.C., on February 23, 1861. By that time seven states of the lower South had already left the Union, and a peace convention in Richmond, Virginia, was trying to forge a compromise under the auspices of former President John Tyler. Lincoln gave the delegates to the convention no encouragement, however.

Lincoln took the oath of office on March 4, 1861. “We must not be enemies,” he pleaded with Southern leaders in his inaugural address. He reminded them that no state had a right to leave the Union “upon its own mere motion” and warned that he had taken an oath of office to enforce federal laws. “In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war.” He rejected the Crittenden Compromise, which would have permitted slavery in the Western states below the Mason-Dixon line. Lincoln would allow slavery to continue where it already was but would hear nothing of extending it across the lower states to the West.

After his inauguration Lincoln informed the governor of South Carolina that he would resupply the federal garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor with ammunition, food, and medicine, but would send no reinforcements or weapons. On April 12, 1861, the South Carolina government responded by opening fire on Fort Sumter. Thus the Civil War began.

Congress was not in session, and Lincoln did not call it into emergency session. Instead, relying on his own Presidential powers, on April 15 he proclaimed a blockade of Southern ports, called on the states for 75,000 volunteers to join the army and enforce federal laws, suspended the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus (so that he could arrest and hold people without taking them to court), rounded up thousands of Confederate sympathizers in the border states, and spent funds from the U.S. Treasury without obtaining congressional appropriations. Then, on July 4, Lincoln called Congress into session and informed the legislators of what he had done. Within the month Congress retroactively ratified his actions.

Despite his military inexperience, Lincoln displayed a shrewd grasp of military strategy, recognizing from the beginning the importance of the western theater and the necessity of taking advantage of the Union's superior resources. It took him several years, however, to find competent generals to implement this strategy.

For several years the war went badly for the North. In July, the First Battle at Bull Run in Virginia was a defeat for Union forces, with more than 3,500 dead and wounded. A campaign to capture Richmond bogged down. The South won victories at Fredericksburg and at the Second Battle of Bull Run. The Union instituted a draft to replace troops fallen in battle. In New York City draft riots showed strong antiwar sentiment among many Northerners. But eventually the war effort succeeded. In 1862 Union forces led by Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Don C. Buell began to win victories along the Mississippi River, and Admiral David Farragut captured New Orleans.

On the issue of emancipation, Lincoln moved cautiously, insisting that his main priority was to save the Union. As the war continued, however, he became convinced that undermining slavery would weaken the Confederacy, and on January 1, 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The proclamation applied only to areas under Confederate control, and its legal impact was uncertain, but it redefined the nature of the war and was of great symbolic significance. Furthermore, as Union forces advanced into enemy territory, former slaves became a decisive source of manpower for the Union forces.

In 1863 the fortunes of war turned toward the North. On July 3, Union forces defeated more than 90,000 troops led by Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The following day Grant divided the Confederacy with the capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi. President Lincoln named him commander of the Union armies early in 1864, and he faced off against Lee in Virginia, taking huge losses but steadily moving forward. Meanwhile, General William Tecumseh Sherman began a successful march from Tennessee into Georgia, eventually seizing and burning Atlanta.

On November 19, 1863, Lincoln delivered his famous Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. In 272 words, and three minutes, Lincoln asserted the nation was born not in 1789, but in 1776, "conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." He defined the war as an effort dedicated to these principles of liberty and equality for all. The emancipation of slaves was now part of the national war effort. He declared that the deaths of so many brave soldiers would not be in vain, that slavery would end as a result of the losses, and the future of democracy would be assured, that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth." Lincoln concluded that the Civil War had a profound objective: a new birth of freedom in the nation

Lincoln however seemed certain to be defeated in 1864. His record on civil liberties provoked protests, public opinion remained divided over emancipation, even Republicans lacked confidence in him, and most important, no end to the war was in sight. The election would decide whether or not the war would continue. Lincoln received the Republican nomination and chose the military governor of Tennessee, Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, to run with him on a coalition Unionist ticket.

Democrats challenged Lincoln's exertion of Presidential power, called for a halt to hostilities and the return of slave-holding states to the Union, and nominated General George B. McClellan, whom Lincoln had relieved of command. Successes in the field, especially the capture of the last port on the Gulf of Mexico at Mobile Bay by Admiral Farragut, led many voters to believe the war would soon be over. Lincoln won 55 percent of the popular vote and almost all the electoral votes in the election.

Lincoln's second inaugural address stressed a policy of reconciliation toward the South. In 1864 he had vetoed the Wade-Davis Reconstruction bill passed by Congress because he opposed its harsh terms. Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Virginia reestablished state governments and petitioned Congress for recognition but were denied. On April 11, two days after Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Grant, Lincoln again called for the former Confederate states to be readmitted to the Union on lenient terms.

On the evening of April 14, 1865 while attending a performance of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre in Washington, Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth, an actor and Southern sympathizer, and died the next morning. As his body was taken back to Springfield, mourners lined the 1,700-mile route to pay their respects to the Great Emancipator.

Using military force to defeat the Southern secessionists and win the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln acted in accordance with his oath of office to preserve the Union. In doing so, he used emergency powers that no previous President had exercised. His twin policies, emancipation of slaves and reconciliation of North and South, were his greatest legacies to a war-torn nation.

Lincoln is justly considered the greatest American president. He was a masterful politician, sensitive to and yet constantly shaping public opinion, skilled at balancing competing considerations, and extraordinarily adept at getting rival groups to work together toward a common goal. His leadership qualities were demonstrated in his brilliant handling of the border slave states at the beginning of the fighting, in his defeat of a congressional attempt to reorganize his cabinet in 1862, and in his defusing of the peace issue in the 1864 campaign when he maneuvered the Confederacy into rejecting negotiations. Never losing sight of the larger aims of the war, he remained flexible in his approach to problems, as evidenced by his evolving policies on emancipation and Reconstruction. Nevertheless, the toll of the war was visible in his haggard face: he stoically endured more than any other president personal slights, public ridicule, and criticism beyond the bounds of all decency, had his hopes dashed by one humiliating military defeat after another, and suffered deep personal anguish over the mounting casualty lists. Yet he never faltered in his resolve to persevere to victory.

Uncorrupted by power, Lincoln enunciated the nation's loftiest ideals during its darkest moment. The Gettysburg Address ranks as the supreme statement of the meaning of the war, and his second inaugural is testimony to his humane spirit. For the American people, his life from log cabin to White House epitomizes the American experience, and he has become the national symbol of democracy.