The Presidents of the USA

| Born | Oct. 5, 1829, Fairfield, Vt. (or Waterville, N Y) |

| Political party | Republican |

| Education | • Union College, B.A., 1848 • read law in New York City, 1853 |

| Military service | quartermaster general and brigadier general of New York militia, 1861-62 |

| Previous public office | ♦ collector of the Port of New York, 1871-78 ♦ Vice President, 1881 |

| Died | Nov. 18, 1886, New York, N.Y. |

Political enemies claimed that Chester A. Arthur was Canadian-born and therefore ineligible to be president of the United States. Arthur himself never replied to the charges and said that he was born on Oct. 5, 1830, in Fairfield, Vt., the eldest of seven children of a Scotch-Irish Baptist minister.

He was educated at Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., taught school, and studied law. Moving to New York City, he built up a successful law practice and became interested in Republican party politics.

Arthur rose steadily, if undramatically, in the Republican party by virtue of his willingness to perform the less exciting labors necessary to building a new political movement. As the protégé of the NY state's governor he served as engineer in chief, inspector general, and quartermaster general of New York, raising, equipping, and dispatching state troops for the Federal government. In 1863, when the Republicans were turned out of office, he stepped aside for a Democratic successor. By unanimous agreement he had been an excellent administrator.

As a reward for his work for the party, in November 1871 President U.S. Grant named Arthur to be collector of customs for the Port of New York. In an age when political parties functioned almost primarily for patronage - the jobs and other "spoils" which accrued to the party in power - Arthur possessed one of the most powerful and lucrative positions in the patronage apparatus by the time he was 41. He controlled 1,000 jobs, which he gave to party regulars. Later, President Rutherford B. Hayes forced him out as a reform measure.

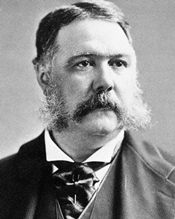

Arthur's nicknames - "the Gentleman Boss," "the Elegant Arthur," - indicate the figure he cut. Over 6 feet tall, stoutly built according to the specifications of the times, with a wavy moustache and bushy side whiskers, he dressed in fine, fashionable clothing. He was exquisitely urbane, dining well, drinking the best wines and brandies, and entertaining on a grand scale. None of this was extraordinary in middle-class New York City, but it made for a stunning contrast to the conservatively clothed and morally straitlaced Midwestern Republican politicians among whom he moved in Washington.

In 1880 Republicans divided sharply and bitterly over the nomination of a presidential candidate. The two principal hopefuls were former president U.S. Grant (Conkling and Arthur were among his chief advocates) and James G. Blaine. The deadlocked convention resolved the issue only by turning to a dark-horse candidate, James A. Garfield of Ohio.

Conkling, the leader of the pro-Grant faction, was furious - for Garfield was close to Blaine- and he insisted that Levi Morton decline the offered vice-presidential nomination. Arthur was the Garfield group's second vice-presidential choice and, though Conkling remained adamant, Arthur accepted. Arthur continued to pay court to Conkling, however, even after the election had made him vice president. In fact, Arthur was in Albany, lobbying for Conkling's reelection, when news arrived that President Garfield had been shot in Washington by a deranged man who claimed he did it in order to make Arthur president. Garfield died on Sept. 19, 1881, and Arthur became president.

Historians tend to agree that Arthur was a much better president than anyone expected. He seemed sensitive to the dignity of his office, and, while he continued to send most patronage to his old allies, he generally distanced himself from their group.

He promised that he would avoid the excesses of patronage appointments that had marked all his career and overhauled the cabinet entirely, replacing all but one of Garfield's secretaries with his own.

His first message to Congress called for the creation of a civil service system, and over the opposition of his Stalwart colleagues he strongly supported the Pendleton Act of 1883, which created a civil service commission and began the principle of hiring on merit rather than party affiliation. He classified 14,000 federal positions, 10 percent of the total, as subject to the merit system.

He vetoed a large rivers and harbors bill that Republicans had passed. He also vetoed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which would have kept workers from China out of the country for 20 years but then signed the measure when the exclusion was limited to 10 years.

Arthur is considered the father of the “steel navy," replacing the “floating washtubs” of the Civil War with modern, state-of-the-art steam warships. This program would give the United States the fifth largest navy in the world by the turn of the century.

As H. Wayne Morgan (1969) points out, "Arthur liked the appearance of power more than its substance." He designed a flag for himself, relished military ceremonies, refurbished the shabby White House, and presented a perfect presidential appearance.

His major mistake was in foreign affairs, when he signed a treaty with Nicaragua to build a canal, in violation of the existing U.S. treaty with the British. The Senate refused to act on it, and President Grover Cleveland later withdrew it. “It would be hard to better President Arthur's administration” was Mark Twain's verdict.

Unfortunately for Arthur's political future (he would have liked to be reelected in 1884), he had alienated old supporters without winning over old enemies. In 1884 he had no real strength at the Republican. Roscoe Conkling had broken with him over civil service reform and other issues, and Grant devoted his energies to blocking Arthur's bid for an elected term of his own.

With the knowledge that he was dying of Bright's disease, Arthur did not put up much resistance to James G. Blaine's attempt to win the Republican nomination in 1884.

Arthur returned to New York City to practice law but died soon after leaving office.

Chester Alan Arthur was a loyal follower of the corrupt Conkling political machine in New York State who owed his political positions to connections and party loyalty. Ironically, it was this machine politician who, as President, presided over the creation of the first merit system for the civil service, or government employees.

Despite a tendency to procrastinate, Arthur grew in the presidency and was able to meet its demands.

As a journalist would later write, "No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted as Chester Alan Arthur, and no one ever retired ... more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe."

Although his failing health and political temperament combined to make his administration less active than a modern presidency, he earned praise among contemporaries for his solid performance in office. He remained what he had always been, a good administrator. The New York World summed up Arthur's presidency at his death in 1886: "No duty was neglected in his administration, and no adventurous project alarmed the nation."

By 1935, historian George F. Howe said that Arthur had achieved "an obscurity in strange contrast to his significant part in American history.

The fact is he had not inspired his contemporaries, and, though his biographers have been friendly, he has not inspired them either